By Bernard O’Shea

17/09/14

Every story needs a hero and a villain; Glorious and virtuoso good guys locked in an eternal struggle with villainous, moustache twisting bad guys. Or so they say. The problem with heroes and villains is that it isn’t always easy to tell which one is which.

Take for instance Marvel’s premier team of mutant superheroes the Uncanny X-Men. On one hand you have the founder of the X-Men; Professor Charles Xavier, an advocate for mutant rights by peaceful means he is also a high level telepath and a scientist. On the other hand, you have the X-Men’s arch foe; Magneto, the mutant master of magnetism, he prefers a more militant approach to mutant rights. He also has an affinity for wearing red and he has more civilian names that Tiger Woods has golf clubs. When Uncanny X-Men #1 was published in 1963 that was pretty much how the dynamics of the hero villain relationship was set-up.

Now, I grew up in the ‘90s, therefore I read X-Men comics throughout most of that decade. I was also present for the video games, the animated show, and the comics based on the animated show. However, there remains one constant throughout this period. I never liked Professor Xavier; in fact I will go as far as to say that I found him to be really annoying. I thought it was just the way he was being portrayed in the comics that I read at the time, but I’ve since gone through the back issues and it hasn’t altered my opinion.

As I’ve grown into an adult I will even go as far as to say, and I paraphrase two well-know podcasts on the topic of the X-Men, when I say, I think Magneto had some valid points. He has an interesting back-story and his ideology isn’t totally dissimilar to Xavier’s contrary to popular belief. Maybe I’m becoming more of a cynic as I get older but I am identifying more with Magneto these days.

Professor Xavier and Magneto have traditionally been labelled as representing people on opposite sides of the divide. Most famously they have been compared to Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, however such a comparison is lazy, ill-informed and insensitive to the real life Civil Rights Movement and the politics therein.

Nothing is ever as black and white as it seems, and when I did take the time to review past issues of Uncanny X-Men I personally felt Xavier wasn’t always the ‘good guy,’ his students may have felt he was.

Therefore I will now conduct a simpler exercise to determine who the bigger villain is; Professor Charles Xavier or Magneto.

The rules are simple; there will be three rounds, (like a good amateur boxing match), in each round I will explore the stories featuring both characters from a specific era e.g. Silver Age, Bronze Age and the Modern Age. In order to determine a winner of each round I will score them based on number of deaths attributed to a character, property damage or the inexplicable hurt caused by them to others.

On occasion I may have to refer to stories out of sequence, but only to lend some sense of linear storytelling to this article. Don’t get blame me, blame the sprawling history and inconsistent continuity of the X-Men franchise.

so here we go…

Round 1: The Silver Age (1956-1970)

Professor Xavier:

Let’s start with Professor Charles Francis Xavier, the founder, mentor and leader of the Uncanny X-Men. I already hear the cries, “How can Xavier, possibly be a villain?” Well if the Silver Age is anything to go by there is plenty of evidence to suggest that his heroic front is a little more ambiguous than it seems. People may say I am mad but let’s face it there was a team of professional writers and editors in charge of the title, so any repercussions from what I am about to write must be laid at their creative doors respectfully.

Xavier first appears in X-Men Vol. 1 #1, this was the premier issue that introduces the original five X-Men as well as Magneto. The problem with the Silver Age X-Men is that a lot of the stories aren’t very good, the characterisation took a long time to establish and mostly what people associate with being good about X-Men didn’t appear until Giant Sized X-Men #1, in 1975 when Len Wein and later Chris Claremont were writing the series.

That said there is enough action in the Silver Age for the purposes of this experiment. The first issue also gives us a bit of an insight into the deviousness of Professor Xavier. X-men #1 begins with the original team meeting Jean Grey aka, ‘Marvel Girl,’ this was supposed to be her first visit to the X-Mansion, however as it is later revealed in 1981’s Bizarre Adventures #27, that Xavier had been training her for many years before the events of X-Men #1. It is later revealed that he had been suppressing her telepathic powers, in order to help her to better adapt to them.

This is something I find very strange and creepy, considering that Jean Grey plays along with this façade and does not let the others know of her previous relationship with Xavier. I would be willing to let this pass if not for Xavier’s omission in X-Men #3 that he is in love with Jean, but that he cannot tell her because he is in a wheelchair and she is love with Scott.

Now I don’t know about anyone else, but I think the bigger stumbling blocks are that Jean is underage, Xavier is middle-aged and it violates the whole teacher-student relationship as well as several important laws. The idea seems to have been discarded for a long time, and although Xavier never acted on it, it does cast him in a much different light when you read it by today’s standards.

That aside X-Men #1 set-ups the premise of the series; Xavier is presented as the champion for the peaceful co-existence of mutants and humans. Mutants are the next step in the evolutionary chain, which in the early 1960s are feared and hated because of their difference. You can begin to see how some people feel this is a civil rights analogy, yet this is the very reason I feel that the X-Men flounders in this respect, because there is a distinct lack of diversity in the team, which is made up of largely middle-class, WASP-ish teenagers.

Also a major contradiction for me in respect of Xavier’s dream of peaceful co-existence is his method for achieving it. Does he organise peaceful protests? Does he engage in debates on the issue in the public domain? Does he advocate on behalf of the rights of Mutants? No. He trains them how to fight and he gives them matching uniforms. Technically, under the Geneva Convention, Xavier has created his own Army or at the very least a paramilitary group. It doesn’t sound very peaceful to me.

There is a strong argument that Magneto had to be prevented from launching the nukes in X-Men #1, but come on couldn’t he have phoned the Avengers.

I hope readers are beginning to see where I am going with this. When you stop and think about even the name ‘X-Men,’ it’s a bit self indulgent. I understand that in the first issue he provides some waffle about the ‘X,’ relating to some sort of ‘X-gene,’ present in mutants, but he also claims to possibly be the first mutant. I think he wants the name to be ‘Xavier’s Men,’ I don’t think there’s any doubt about it especially when the guy is arrogant enough to believe he’s the first of his kind. I also like to think Xavier had been reading DC Comics ‘Doom Patrol,’ which debuted in June 1963, two months before X-Men #1 and stole the idea for his team from that series (I jest). Despite all this by the end of X-Men #1, Xavier and the team have foiled the plans of Magneto.

When you examine the Silver Age closely you begin to see some dubious decisions being made by Xavier. His commitment to the peaceful co-existence of mutants and humans appears to be by any means necessary. In X-Men #2 when Teleford Porter aka ‘The Vanisher,’ decides to steal US Defence plans Professor X wipes his memory. Again, that’s a very peaceful and ethical way of dealing with fellow Mutants.

It also sets a precedent for actions that will happen much later in X-Men continuity. It also sets the precedent for the Silver Age, in X-Men #3 Xavier detects a new mutant; The Blob, when he sends the X-Men off to recruit him, he is living with the Circus, the Blob refuses to join the X-Men so they attack them, because if he won’t join you, beat him. When the Circus gang join in and give the X-Men a bit of a pasting, Xavier mind wipes them as well. Xavier also later mind wipes the Mimic in issue #19 because he can’t stand his obnoxious behaviour. Some might say it was all necessary, I say it’s a blatant abuse of his powers and more fitting with the behaviour of a villain.

Something that becomes a bit of a running theme in Silver Age X-Men is people wanting to blow things up. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times, with real life ‘Cold War,’ themes being present in the writing at the time. It just seems every X-adventure in the early issues is to prevent someone nuking someone else.

In X-Men #4 Magneto plans to blow up a South American country; Santa Marco, with his newly formed ‘Brotherhood of Evil Mutants,’ at the end of this issue the plan is foiled but Xavier tells his students that he has lost his powers. It’s all lies because he gets them back in the next issue, in fact he never lost them to begin with, it was all a ruse as part of a ‘graduation,’ test.

Bloody hell professor! these guys have only been together for five issues and you are letting them go off on their own to fight super-powered villains. I definitely think there is a case for child endangerment here given the ages of some of the team at this point. What if things went wrong would he just go off and recruit a new team? Well actually…ahem…we may address that in a further round.

Xavier’s prowess as a villain knows no bounds. If it wasn’t enough to jeopardise his students safety as part of a graduation exercise, after they do defeat the Brotherhood, Xavier takes himself off to Europe to settle a score with the demonically named, ‘Lucifer,’ who is trying to blow up, some stuff, well it’s never really made clear but Xavier feels it’s important to initially abandon five teenagers in his home in order to defeat him.

Around X-Men #10 & #11 we see Xavier allow a cosmic force in the form of the ‘Stranger,’ kidnap Magneto and Toad, without much concern for the well-being of either and we also see some interesting back story for the professor in X-Men #12. This helps provide further insight into the selfish mindset of the Professor.

Xavier’s origin in a nutshell is this, his parents worked on the atom bomb experiments, his father Brian dies in an atomic blast. His mother Sharon marries her husbands lab partner Kurt Marko. Kurt’s son Cain comes to live with them all in the X-Mansion. Kurt is abusive, Sharon dies, everyone hates everyone, Cain especially hates Charles, there’s a fire, Kurt dies. Cain and Charles go off to fight in the Korean war. Cain deserts and Charles goes after him. At this point Cain finds the Cyttorak Ruby and becomes the Juggernaut but the cave he finds it in collapses on top of him. Rather than dig him out Charles thinks it’s best to let sleeping dogs lie and abandon him.

Now it’s a fairly sympathetic back-story but if the flashbacks are anything to go by, and if I was Cain I would hate Xavier’s guts as well. The flashback’s reveal Charles was a bit of a-know-it-all and he wore suits while he was at home, what child does that?! Also it’s enough to be super peeved at someone who abandons you under tons of rubble. I personally like to think there’s some additional beef relating to a will and/or ownership of the X-Mansion that Charlie fails to recount in X-Men #12. At least it would explain why he abandoned Cain in Korea. Inevitably, the Juggernaut is vanquished by the X-Men and some mind blasts courtesy of Xavier.

The remainder of the Silver Age period provides further situations to speculate over the heroic qualities of Professor X.

Following an epic battle with the Sentinels, in X-Men #14-16 Iceman is left in a Coma, around this time Magneto re-enters the fray, hoping to settle his score and start a mutant army using Angel’s parents. Now, against all medical knowledge and ethical practice, Xavier believes the best course of action is to bring Iceman out of his coma, and fight Magneto. I think that justifies another count of child endangerment. Xavier also assists in the kidnapping of an individual, namely Magneto again, by the Stranger, again. Xavier also performs a mind wipe, again, this time on the Angel’s parents at the end of X-Men #18.

If the Silver Age tells us anything it’s that Xavier’s dream for a peaceful co-existence with humans comes at a high cost. He will literally sacrifice his students to achieve it. I feel he’s a fanatic, he’s obsessive with his dream and he will pursue it by any means necessary.

He’s also a bit of a moaner. In the modern age of comics Xavier is representative of the diversity in comic books. In the Silver Age he seemed to spend several issues expressing his angst about being a wheelchair user. In X-Men #23 he develops his own leg braces that help him walk again. Versions of this device will continue to crop up in X-Men continuity right through into the modern age. They never became a regular thing, but the question that is crying out to be answered is if Xavier was such a good guy why didn’t he patent the invention and make it available to the public. If you ask me he’s a selfish git.

Mid point of the Silver Age run of X-Men we see the creepy Xavier return to the fore. In X-Men #32 it’s revealed that Xavier has been keeping doors locked from his students, particularly the basement door as he’s been keeping a comatose Juggernaut down there. It’s a bit Norman Bates if you ask me. It’s also at this point that Xavier considers that he should have acted more resolutely in Korea, and he makes a botched attempt to wake up and reform the Juggernaut. Naturally things go wrong and it eventually leads to Juggernaut joining Factor 3 and that particularly nefarious group kidnapping Xavier.

When Xavier is eventually rescued, his gift to his students in X-Men #39 is new individual uniforms. The only question hanging over the new uniforms is why did Marvel Girl forsake trousers for a mini-skirt? She did design it herself, but if Xavier was acting as an appropriate adult he may have asked her to re-consider. Again, the Silver Age relationship between Charles and Jean seems dubious to me.

Not long after that episode Xavier begins acting more oddly than he has done in any previous issue. He is like a creepy Hitchcok-ian ‘Uncle Charlie,’ only sharing his secret with Jean Grey and throwing mood swings. In X-Men #42 the team go face to face with Grotesk, the subterranean, sub-human supercharged by radiation. He proves more than a handful for the X-Men and so Xavier has to join them in the field to defeat the villain. The climax results in the death of Xavier. He reveals at the end of the issue that he has already been dying of a terminal illness.

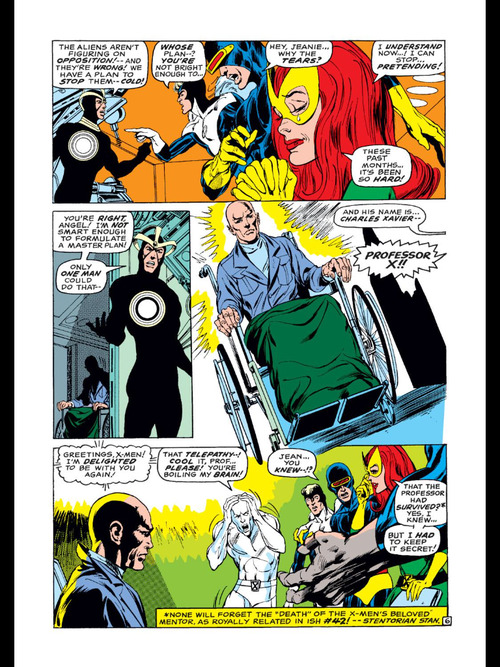

That appears to be the end of Charles Xavier except in 23 issues later in X-Men #65 it all turns out to be lies and Xavier has been hiding out in the basement of the X-Mansion, surviving on fun size Mars no doubt. It had been an editorial idea to kill off Xavier in X-Men #42 as an attempt to counteract poor sales on the title. He returned in X-Men #65 to prevent the Z’Nox alien race from taking over the world. He does this by reaching out across the world to form a cosmic love ray to repel the Z’Nox.

It may have been enough to scare the Z’Nox away but it wasn’t enough to halt declining sales and after one more issue X-Men fell into reprints and went into a five year hiatus until Giant Sized X-Men #1 in 1975.

That concludes the Silver Age in respect of Professor Charles Xavier, so let’s take an account of his misdemeanours so far;

- Training a small army of child soldiers.

- Suppressing Jean Grey’s telepathic ability.

- Inappropriate feelings for his female student; Jean Grey

- Being arrogant and naming the team after himself.

- Ripping off the Doom Patrol.

- Mind wiping people on at least five separate occasions.

- Attempted kidnapping of the Blob.

- Numerous counts of Child Endangerment.

- Party to the human trafficking of Magneto and Toad.

- Abandoning his half-brother under a mountain in Korea.

- Holding his half-brother captive in the basement of the X-Mansion.

- Not sharing his ‘helps you walk again,’ leg braces invention with the wider public.

- Faking his own Death.

- Facilitating the assisted Death of the Changeling.

- Effectively killing off any new X-Men material for 5 years.

Now let’s have a look at…

Round 1: The Silver Age (1956-1970)

Magneto:

Magneto is the most famous X-Men villain; created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby he also made his first appearance in X-Men Vol.1 #1. In more recent years Magneto has gained an almost ambiguous relationship with super-villainy. Some view him almost as an anti-hero of sorts, largely because of his interesting and varied back-story. Stan Lee is quoted as saying, “I did not think of Magneto as a bad guy. He just wanted to strike back at people who were so bigoted and racist…he was trying to defend the mutants, and because society was not treating them fairly he was going to teach society a lesson. He was a danger of course…but I never thought of him as a villain.” Now either Stan Lee has a very bad memory or he has started to ret-con his own memories but if you read the Silver Age Magneto, I can assure you he is very much an out and out crack pot villain.

Most of the depth and characterisation of Magneto is largely established in the Bronze Age by Chris Claremont. It would be nice to think that Stan Lee and Jack Kirby had the ideas all mapped out at the beginning. However, as I see it Marvel in the early 1960s was a conveyor belt of superheroes; a lot of what I see in the Silver Age Marvel titles are rifts off the Fantastic Four and Amazing Spiderman books. The same idea repeated again and again in slightly different ways. That said, the Silver Age Magneto is the most memorable villain, as we can all see from his longevity into the present day.

When we first see Magneto in X-Men #1, he is attempting to capture Camp Citadel a Nuclear Missile base with the rather vague idea of seizing control of the camp as a display of Mutant power. It’s a rather aimless mission, but that’s probably down to this being the first issue and Lee and Kirby wanting to establish the premise and introduce the original characters of the X-Men title.

If it’s one thing we can say about the Silver Age in relation to Magneto it’s that it provides him with his style. During the Silver Age the X-Men changed their costumes numerous times, however Magneto’s red and purple centurion style garb became his defining feature.

The thing I like about Magneto is that he’s a stylish villain, he like the Liberace of super-villains. He is also guilty of the same arrogance Charles Xavier, naming things after himself such as his Magneto car (why he has a car when he can levitate is beyond me) and the coolest liar even; Asteroid M. By the standards of the X-Men title, it seems that in the 1960’s people just stuck their initials on to the names of things to declare ownership rights.

|

| Asteroid M |

Magneto does stop short of naming his group of evil mutants the ‘Magneto-Men,’ instead they are named the ‘Brotherhood of Evil Mutants.’ The ‘Evil-Mutants,’ part aside, the ‘Brotherhood,’ part generates an impression that Magneto’s mutant faction are more politically minded, almost concerned about the socio-political needs of mutants. Historically, there have been political organisations that have been known as ‘brotherhoods,’ e.g. the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) also referred to as ‘The Fenians,’ were an oath bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an Irish Republic which were active between 1858 and 1924.

The Silver Age doesn’t really set the Brotherhood up as a political organisation. Although, I do feel that the idea of a Brotherhood is more consistent with the idea of advocating and promoting Mutant Rights. Magneto chooses to deploy the Brotherhood as another paramilitary style organisation but I feel to give him credit he is, to an extent, sheltering and safeguarding Mutants under the banner of the Brotherhood. In this sense, despite his character flaws he is more consistent with his message than Xavier. He’s not operating a personal strike force on the pretence that they are being used in a violent struggle to achieve a peaceful co-existence.

The Brotherhood, make their debut in X-Men #4. The original members are Toad, Mastermind, Quicksilver and the Scarlet Witch with Magneto as the leader. Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch are portrayed as the reluctant villains, however it is worth remembering that Magneto saved them from an angry European lynch mob, the kind that used to roam the Marvel Universe up until the late 1980s. There membership of the Brotherhood is as a result of their feeling that they have a debt to repay. I feel in respect of the pair it lessens the idea that Magneto is a villain that coerces Mutants into joining him. It stands in contrast to the X-Men’s violent, attempted recruitment of the Blob in X-Men #3. I just feel that despite the lack of any real characterisation for Magneto in the Silver Age, on occasion his values are more consistent with his actions than perhaps Xavier’s are.

That said I’m pretty sure that Stan Lee only envisaged Magneto as a villain in the early days. X-Men #4 involves Magneto planning to blow up a South American country. As per his first appearance the plan is suitably vague and it doesn’t come to fruition. He does manage to kidnap the Angel in X-Men #5 which results in a battle with the X-Men on Asteroid M.

X-Men #7 sees Magneto come into contact with the Blob. If you recall Charles Xavier mind wiped the Blob in X-Men #3 so Magneto helps the Blob get his memories back and then he offers him a place in the Brotherhood to get revenge on Charlie and the X-Men. In fairness, if I just remembered that someone had mind-wiped me and I had lost a significant period of my life I’d be pretty ticked off and want to settle a score so I don’t think that Magneto can be blamed for putting the Blob up to anything.

X-Men #11 is interesting because it includes an appearance of the cosmic being known as the ‘Stranger.’ The Stranger is a peculiar character because at this point he is very much a Sci-Fi inspired character; he had appeared in the Fantastic Four but had never been given a proper origin or explanation. He appears at a point in X-Men history before the whole space opera style stories were a regular feature. He seems a bit out of place in the title. Anyway, to cut a long story short, the X-Men and the Brotherhood both try to recruit the Stranger and the end result is that he takes a shine to Magneto and the Toad and decides to take them back to his home planet and place them alongside his other other-worldly collectibles. Essentially, the ‘Stranger,’ is a cosmic Human Trafficker. None of the so-called heroes in the vicinity attempt to stop this, so we can only assume from this episode that Xavier would rather see Magneto out of the picture than as part of his peaceful co-existence dream.

When Magneto next appears it’s in X-Men #17 and essentially the story plays out as Home Alone, only Magneto plays Macaulay Culkin’s part as Kevin. Basically, there is a stranger lurking in the X-Mansion setting up deadly booby traps like greased up floors etc and the X-Men can’t figure it out. At the end of the issue it’s revealed to be Magneto. Apart from breaking and entering and being in breach of health and safety, all in all it doesn’t add up to much of an evil plan.

Rather it appears to be a set-up for his real plan to create a clone army using Warren Worthington’s parents. One of the frustrating things about Magneto, and something that is quite apparent in the Silver Age is that there is no consistency with how his powers are written. Magnetism is seemingly a by word for any superhero power that can be given to him for the purposes of storytelling. In X-Men #18 he is able to hypnotise the Worthington’s with his ‘magnetic personality.’ It’s a bit of a stretch to be fair. Safe to say the Clone army never get’s off the ground, Magneto fights to a standstill with Iceman before being defeated by the rest of the X-Men and re-captured by the Stranger.

When Magneto resurfaces in X-Men #43 we first see him rejoicing in the death of Charles Xavier. A very villainous thing to do, but, when viewed in light of later continuity which sets up their relationship as friends, then I’d be pretty happy that my one-time friend, who has basically ignored the fact that we were friends for 43 issues, and who was happy to allow me to be human trafficked, had passed away.

When the issue begins it is worth noting just for the purposes of continuity that Magneto has been off tussling with the Avengers. In Avengers #47-49 Magneto has escaped the Stranger’s prison with the Toad. He regroups the Brotherhood and demands his own island nation for Mutant-kind. To me it sounds like his best plan yet, but as always he gets beat down by a team of superheroes. It’s revealed in X-Men #43 that Magneto has secretly coerced Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch into re-joining the group. During the battle with the Avengers he uses his powers over magnetism to deflect a bullet, so that it grazes the Scarlet Witch. He then promises to develop technology that will heal hear. I guess Mutants in the 1960s were funny about basic first aid and visiting the hospital, but anyway.

The story which begins in X-Men #43 runs into X-Men #45 and crosses over with Avengers #53. The story in a nutshell is that Magneto has developed a new niche; stealing cargo ships and using their contents to build his own mind control device for the purposes of taking over the world. At this point he is hiding out with the Brotherhood (minus Mastermind and the Blob), on a secret island location. The X-Men find it and promptly get captured. Angel escapes and goes to the Avengers for help; Cyclops also has a fist-fight with Quicksilver.

In between all that we see Magneto being really nasty to Toad. Now it’s probably fair to say that despite taking mutants into the Brotherhood, Magneto has been a bit of an ass to everyone. For months he allowed Mastermind to sleaze around the Scarlet Witch and he generally thrown his weight around and insult everyone whilst all the time demanding their undying loyalty. In this story he really lays into Toad, maybe he’s just antsy because he had to spend several months with him locked in a glass cabinet, but it’s really unfair to Toad. At one point in Avengers #53 he says to Toad, “I’ve kept you around because you are so laughingly, fawningly pitiful.” It maybe doesn’t sound too bad by today’s standards but Toad’s thin skinned. In the end it all backfires on Magneto as he is defeated by the Avengers and the X-Men and Toad decides to get his own revenge by blowing up the island base making his escape in a plastic ship, the reason being Magneto can’t use his powers to levitate onto and escape. The final panels depict Magneto falling to his doom.

In X-Men #49-52 the villainous Mesmero, reveals that Bobby Drake (Iceman’s) new girlfriend Lorna Dane (Polaris) is really the daughter of Magneto and has her own magnetic powers. Magneto shows up but the big reveal turns out to be that it was all a lie concocted by Magneto, Lorna is not his daughter he had just been fooling in order to make use of her magnetic powers. The fiend. Strangely enough the action all takes place on another island and at the end Magneto blows it up. It’s becoming a regular occurrence for Magneto to do this which must really annoy the people who draw maps, without even considering the ecological and environmental damage he must be causing by blowing up all his bases.

Magneto can be perhaps pardoned for that last crime as it is later revealed in X-Men #58 that the Magneto that Mesmero was working for was really a robot. The real Magneto appears to be missing in action.

It’s not long before he turns up again. Following an adventure in the Savage Land fighting Sauron, the X-Men encounter Magneto again in X-Men #62. This time he’s self-styling himself as the ‘Creator.’ By this stage his evil plans are becoming more elaborate. He wants to raise a mutant army to conquer the world. When he first re-appears, he is out of costume and he rescues the Angel from a dinosaur attack. At this point no one recognises him until he puts on his helmet. He gives Angel a new blue and white costume but that’s just so he can use it to drain energy from him. His plan in the Savage Land amounts to genetically engineering new mutants. His plan is foiled by the X-Men who bash up his base ruining his power source which depowers his Savage Land mutates and causes them to revert to their normal form. In this sense his crime of genetically engineering new mutants is lessen as it seems the changes are really just cosmetic or augmentative at best.

X-Men #63 proves to be Magneto’s last Silver Age appearance in an X-title as X-Men went into hiatus for five years. So at this point it is worth adding up Magneto’s list of crimes against humanity;

- Taking control of a Nuclear Missile base by force

- Attempting to blow up a South American country

- Breaking and entering of the X-Mansion

- Violating Health and Safety procedures in the X-Mansion

- Coercion and holding the Worthington’s Captive

- Child Endangerment

- Coercing the Scarlet Witch and Quicksilver into re-joining the Brotherhood.

- Attempted mind control

- Bullying and emotional abuse of the Brotherhood.

- Emotional blackmail of Polaris (later attributed to robot Magneto)

- Causing serious ecological and environmental damage by blowing up at least two island bases. (Although technically, Toad blew up one and Robot Magneto blew up the other one).

- Genetically engineering/augmenting a Mutant army.

- Attempting to take over the world with a Mutant army.

So after one round the verdict is…

Professor X is the biggest villain!

So many of you will be jumping up and down and shouting at the result, but I just feel that Charles Xavier is the bigger villain. Magneto has been clearly portrayed as a villain and many of his schemes are a direct threat to both human and mutant kind.

However, that does not excuse the fact that Charles Xavier is claiming to be a pacifist yet operates a clandestine personal strike force. He has also mind-wiped several individuals, which raises important questions about his real ethics, values and motives. Plus there is all that angst and unresolved issues relating to Jean Grey, it’s all a bit overwhelming for me as a reader.

At least Magneto is consistent. I am not saying he’s not a villain but I just feel Xavier is a bigger villain.

That said, it’s still all to play for, as there are two more rounds to go before we finally decide who is the biggest villain; Professor Charles Xavier or Magneto?

Next Time: The Bronze Age!

If you are a long-tine X-Men fan or would like to learn more about them then you may enjoy the’ Rachel and Miles Xplain The X-Men,’ podcast. It provides an in-depth look at the X-Men comics, movies and animated series. It’s a lot of fun. Check out the website; http://www.rachelandmiles.com/xmen/